Fire is seen as purifying in all cultures, and the fire festivals involve many rituals, legends, myths, and beliefs that were of symbolic importance for previous generations. Three elements in particular–fire, water, and the plant world–were seen as particularly important. As we have seen in fire festivals around the world, fire has an important symbolic power in religions, myths, and social celebrations.

While all community celebrations tend to be cathartic, the solstice festivals can also be seen as way of marking the passing of generations and young people’s coming of age. Fire was also believed to ward off evil spirits and the ashes were used to fertilize the land. These ancient beliefs underlie the festivals that are celebrated today.

Burnt embers used to protect people’s home

There are still people today who use the charred wood and ashes from the bonfires to protect their homes and to fertilize their vegetable gardens. It was believed that the bonfires, falles, and smoke frightened evil spirits away as in the distant past. In Isil, fallaires draw crosses on the cemetery gate, a custom related to old protective beliefs. And in many Occitan villages, young people rub ashes on their faces when the fires have burnt out. In Bagà, falles used to be burned in front of all the houses, as the smoke was believed to protect the house from evil spirits. These beliefs are now little more than stories, but they are part of the heritage of the inhabitants of the Pyrenees. Every year they repeat these captivating magical rites in which fire plays a central role.

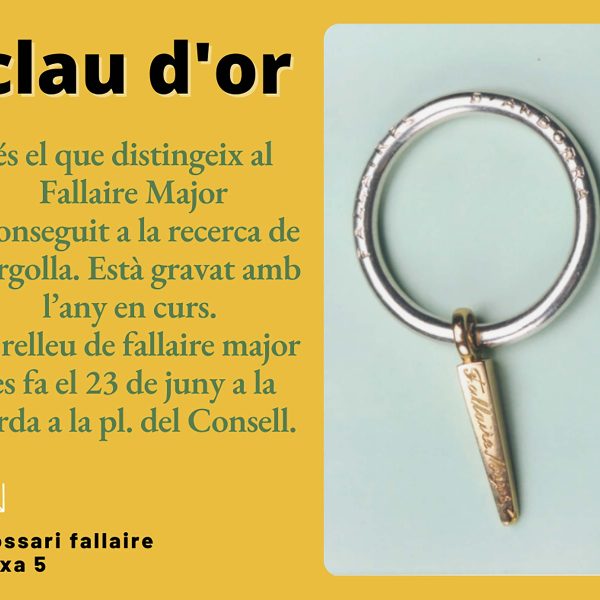

Charlemagne’s ring

In Andorra, the fallaires go up to the Fontargent pass, which is the dividing line between Andorra and the Ariège region of France. The fallaire major (the Senior fallaire) is always elected on the first weekend of June and the various candidates, accompanied by a team, must find the golden nail hanging from a silver ring that has been hidden in the Incles Valley. The legend tells that when Charlemagne crossed Andorra over the Fontargent pass, he nailed a ring into the rock in order to tether his horse. This nail is believed to turn into gold every Saint John’s Eve. And for this reason, the fallaire major wears it around his neck.

Legends about the falles

There are numerous legends related to the fire festivals. In Isil, a legend tells that the festivities began in 1487 when the Countess Caterina had to flee from the castle in València d’Àneu to France and was led by a group of peasants carrying torches. In the Aragonese Ribagorza, another legend recounts that the torches scared off the Saracen troops, so they never reached the Pyrenees, much like the Andorran legend, which attributes their flight to their balls of fire. All these legends, and many others, tend to mythologize the falles by linking them to historical episodes.

The healing properties of plants and water

Saint John’s Eve is associated with a number of rituals, practices, and beliefs, whose origins and historical and social background are not known.

Although there are differences from one locality to another, there are a number of elements in common: fire, water, herbs, and spells . . . The medicinal properties of plants were believed to be more effective if they were picked on Saint John’s Eve: “Saint John’s, good for the whole year,” as the saying goes. It was also thought that the magic of the night could help to cure specific ills such as warts and hernias

Many people also bathed for luck, or rolled in the dew-covered grass to cure them of their ills or protect them from infection. Bathing in rivers and lakes was a rite that provided protection and healing or acted as a break with the past and the beginning of a new and better time. Saint John’s Eve continues to be a time of rituals, customs, beliefs, and practices … all of which make it a “magical night.”

Occitan

Occitan