The Pyrenean fire festivals are almost certainly very ancient, although they have evolved over time. In the first half of the 20th century, interest in the festival grew as a result of work by folklorists and other scholars. It then went into a period of decline, however, as a result of depopulation in the Pyrenees, and many villages ceased to celebrate it altogether. In some cases, it was kept alive by children.

The festival underwent a renaissance in the 1980s, when it took on greater importance as a symbol of local and Pyrenean identity. In the 1990s and early 2000s, many festivals were reinvented in their current formats, and even spread to other villages. The reinvention of the festival meant adapting it to current times, with a concern for sustainability, adapting to tourism, and gender equality. Fire festivals are increasingly looking to the future.

Little documentary evidence about the origins of fire festivals

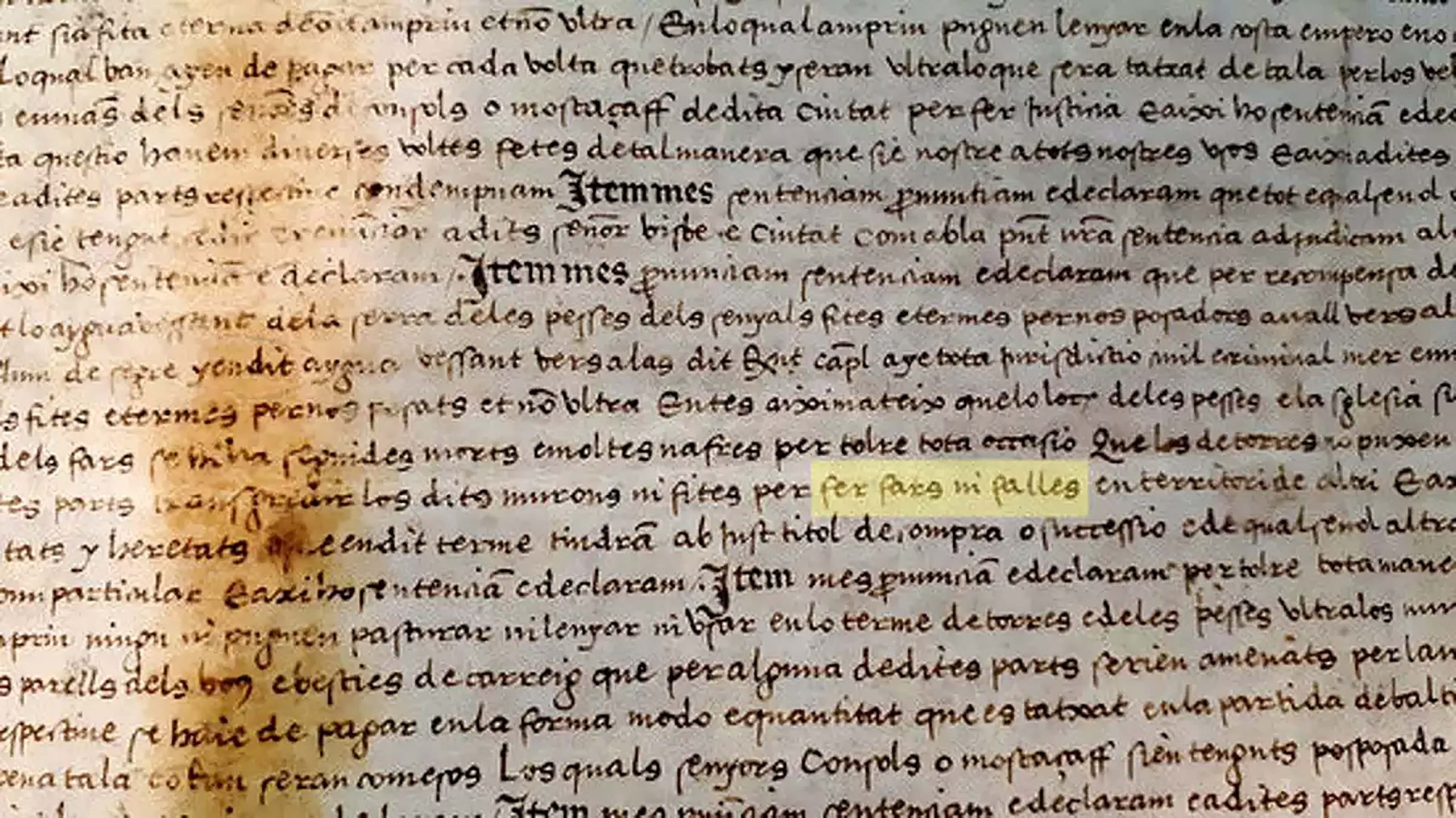

The origins of the fire festivals are lost in time. According to Xavier Pedrals, a tenth-century document from the Archive of the Abbey of Montserrat told us about the place where the Falles descended in Bagà, in a tower still preserved where the fire would be symbolically lit. More accurate references to the falles would be found in a document found in the Alt Urgell archives by Carles Gascón. The document refers to a ruling by the Bishop and Chapter of Urgell and the city concerning conflicts between two villages, Torres and Alàs, which, according to the text, had erupted over where to locate the respective beacons and falles processions and had caused deaths and injuries. The ruling stipulated that henceforth the residents of Torres and Alàs could only hold celebrations within their own municipal boundaries. Other reference is a document in a 1763 document from Vilaller.

According to historian Serge Brunet, French judicial archives in Toulouse attest to a dispute between Sant Bertrand de Comenge and Valcabrera (Haute-Garonne) in 1344 during the celebration of the feast of St. John. Although some sources mention the presence of brandons in the Modern Age, the most detailed descriptions are not found until the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th. As Riart and Jordà have pointed out, it is curious that documentary evidence is so thin until the late 19th century.

Document referring to the falles. Alàs, 1543 (Arxiu Comarcal de l’Alt Urgell)

Interest in the festivals by Catalan, Andorran, and Aragonese scholars of folklore

In Catalonia, Andorra, and Aragon, it was folklorists who made the first detailed descriptions of the fire festivals.

In 1896, the Aranese writer Jusèp Condò Sambeat published an article for the Centre Excursionista de Catalunya describing the halhes, although he didn’t specify the location. Condò explains: “To those who have never seen them, they look like demons escaping from hell, especially when seven or eight villages can be seen. When the celebration is over, villagers all take the falla, now blessed, to their kitchen gardens, where it is believed to improve their crops.

One of the oldest accounts is Joaquim Morelló’s description (1904:169) of the festival in Isil: “one of the typical customs of the locality is that of the falles, which consists of running with lighted falles from a certain point of the mountain to the village. The falla is a trunk of young pine split at one end and studded with resinous pieces of wood. At the entrance of the village, the men carrying the falles are awaited by the girls, who give them a bouquet of flowers and a glass of wine. When everyone has arrived in the square, the falles are thrown in a heap to create a bonfire. The girls begin to dance a sardana around the fire, and in the words of the songs invite the men to join in.”

Joan Amades describes the festivities of several Pyrenean villages in the period from 1941 to 1948, especially those in Isil, Esterri d’Àneu and Vilaller. He writes that “this custom, especially in Isil, is still very much alive, and in 1949 there were 53 fallaires” (1953, vol. IV:51). He says that the falles are principally a festival for “la fadrinalla” (the young people of marriageable age). He also gives descriptions of the balls of fire in Andorra and the Aran Valley. Later, in 1958, he comments that “the children make falles out of poplar and birch bark, which they whirl in the air with dizzying speed, producing the effect of a wheel, scattering light and sparks into the darkness. In the middle of the immense woods, these falles produce an effect that is truly Dantesque!”

The earliest descriptions of the festivals in Occitania

A number of folklorists and local scholars in Occitania also studied these customs, sometimes from a Romanticist point of view and sometimes in terms of their symbolic nature. Scholars like Édouard Piette and Julien Sacaze (1877), founder of the Société des Études du Commenges, related them to primitive customs. In La montagne d’Espiaup (1877: 249-250), they pointed out that “the primitive cult of fire has left many traces in the Larboust Valley. Christianity has appropriated and sanctified certain practices, but in several localities, the primitive cult still exists and the inhabitants practice it unwittingly. Today, in the commune of Cazeaux-de-Larboust, from June 20 or 21, the shepherds gather on the ridges of the Arrouy mountain for four or five nights in a row (…) As they walk from the Bach de Cadaou to the village, each one carries a fir brandon (halha) and whirls it around in circles that produce balls of light.

Until recently, in Castillon-de-Larboust, when the priest lit the fire in the brandon near the village on Saint John’s Eve, a rival brandon was lit on the mountain, at the top of the Artigom (…) This is still done in Luchon (…) but only young people and children take part in celebrations that also involve dancing and wild screaming. In all the communes of Larboust, the Saint John’s Eve brandon is erected a year in advance by the most recently married couple. In Luchon they have the curious custom of enclosing snakes that escape hissing when they sense the flames rising towards them. A widespread belief in the Larboust is that a small piece of charred wood from the brandon wards off lightning and evil spirits from the house, where it is piously preserved.”

The festivals in crisis

In spite of its antiquity, the festival went into decline at the end of the 19th century. On a visit to El Pont de Suert at the end of the 19th century, the Graus pharmacist, Vicente Castán, commented “Everything is disappearing, and the traditional falles have lost importance with the passage of time; only a few people remember what they once were.” It was in the post-war years that the festival declined precipitously on both sides of the border; the exodus from rural areas caused a crisis in Pyrenean society, and many festivals ceased to be held in the 1950s and 60s.

The falles survived in the villages where they were part of the annual village festival, and in other places, like Isil, they survived in part due to the work of folklorists, especially Ramon Violant i Simorra. But even Isil went through some difficult years when the village had very few people to make and bring down the falles.

On the French side, the break is not as radical: those in charge of the festivities claim that, with the exception of a few years (2013 due to floods, and 2020-2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic), the festival has been celebrated without interruption. The territory where the fire festivals were celebrated used to extend well beyond the current Barousse and Comenges, however, approximately south of a line connecting Lanamesa with Saliàs deth Salat. This practice diminished during the 20th century and the brandons are now celebrated in a much smaller area.

Revival and reinvention of the festival

In the 1990s, and in some cases the early 21st century, the festivities were recovered in many villages, which updated and even reinvented many practices. The rediscovery was driven by different factors: assertion of local and regional identities in Catalonia and Andorra, economic expansion of Pyrenean villages due to tourism, and an awareness of the capacity of intangible cultural heritage to forge a cross-border Pyrenean identity. Since then, the festivals have been promoted and revived in an increasing number of villages and towns.

The process has not been the same in all the villages, however, and while in some villages they continue to be limited to the local community, in others they have attracted tourists in huge numbers. Despite these differences, there are three key aspects: the desire to promote local identity in a global society, the involvement of new generations keen to revive the festivities, and the growing prestige of the fire festivals amongst the population. And in all cases, the updated celebrations have emphasized common elements such as the descent of the falles and the brandons.

Falles Isil, 1986. TVE Comarques

Heritagization of the fire festivals and inscription on the UNESCO list

The fire festivals are now also considered to be intangible heritage. The governments of Catalonia, Andorra, Aragon and France have all officially defined them as heritage, which helps them to gain recognition and prestige. What really made them famous, however, was the application to UNESCO for world heritage status in which festivals were defined as a mark of cross-border Pyrenean identity. The application, which was presented by the Government of Andorra, brought together 63 villages and towns in Andorra, Catalonia, Aragon and Occitania in which fire festivals take place.

The application involved a collaborative effort amongst the fallaires communities and governments, an exercise in geopolitics, and the creation of a common discourse for festivals that have much in common but also many differences. Even coming up with a common name (in the end, the “Pyrenean Summer Solstice Fire Festival) was a challenge.

After UNESCO

Since being inscribed in the UNESCO list, the fire festivals have evolved in a number of different ways. On the one hand, there have been numerous meetings of the various different communities, especially thanks to the Pyrenean Fallaires Municipalities Cultural Association (in Catalonia and Aragon). A cross-border coordinating committee has also been created. In 2017, Andorra fallaires groups came together to form created a national falla board, whose aim was to safeguard and promote the falles.

The board works together with the Department of Cultural Heritage in Andorra to promote the festival and enable it to survive. This enables Andorra to ensure the direct involvement of the largest possible number of associations, groups, and individuals in the management of the festivals.

Recent studies on the fire festivals

There have been numerous studies and publications on the festivities by a number of different authors: Sergi Ricart and Xavier Farré (2012 and 2016), Jordi Alsina and Lluís Ràfols (2019), Oriol Riart and Sebastià Jordà (2015), Albert Roig (2017), Xavier Pedrals (2007l, 2017), Mireia Guil (2021), Patricia Heineiger-Castéret (2017), Roberto Serrano i Xavier Farré (2017), Bernat Menetrier (2018), and many others. Consult the bibliography section of this Virtual Museum.

A large number of videos, reports, and news coverage has also been produced recently, many more than previously.

Fia faia. Bagà, 2021. Photography: Xavier Roigé

Occitan

Occitan