The festival in Occitan villages revolves around the burning of a large pole that is erected in the village square or in an open field.

The pole is referred to variously eth har, eth halhar, eth haro, eth taro, or el brandó in the different languages and dialects. In some Catalan or Aragonese villages, a trunk, called a falla mayor or a faro is also raised in the village and is set alight when the fallas arrive. In some Aragonese towns, two bonfires are built, one in the town square and the other at the starting point of the descent.

The brandon festival is the main community festival in all the towns that celebrate it. Unlike the individual falles, here the whole celebration is collective and the inhabitants of each village renew their community and social ties, reinforcing their identity around the fire.

In Occitania, this festival is celebrated in more than 90 villages, although only a third are officially registered with UNESCO.

The brandon in Commenges and Barousse

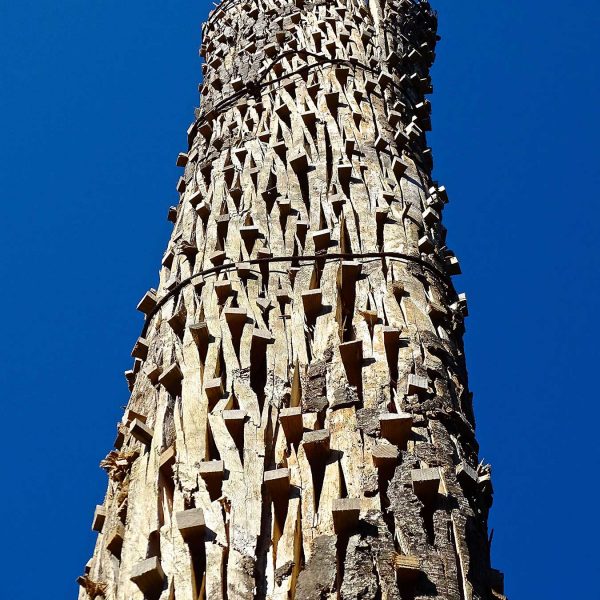

The brandons in the Commenges and Barousse regions of Occitania are made using traditional techniques.

The brandon is cut down and split lengthwise with wooden wedges. It is then left to dry for several months before being lit on Saint John’s Eve. Some of the logs are heavily worked, such as that in Régades (with 800 wedges), while others are simpler, with a few slits being made in the wood. The brandon is set alight by a recognized personality, mainly a local person, a priest, the head of an association, or a person called “John” (as in Bertren and Bezins-Garaux).

The center of the tree burns slowly, with the flames escaping through a kind of chimney created when the tree is split. Various people and groups are involved in preparing the tree and organizing the festivities: the technical services, the City Council, the festival committees, various families, local associations, and volunteers. The festival has been passed down by families from generation to generation, although associations are also heavily involved.

The festival in Bagnères-de-Luchon is one of the best-known. It has only been cancelled three times since records began: in 2013, due to floods, and in 2020 and 2021 due to Covid. The town council plays a very important role in supporting the festivities and in advertising the festival. Year after year, the brandon is set alight in front of the thermal baths in Luchon, and the festival is also celebrated in all the villages in the area. The mayor and the parish priest, who have joined the parade, light the brandon together. It burns fiercely for about an hour before collapsing amidst a shower of sparks.

At this point, the young men run to the fire and grab a scrap of wood which they whirl in circles it in the dark of the night and chase the young girls in an attempt to smear them with ashes. Many people take a small piece of charred wood home with them because they believe it will bring good luck to the whole household throughout the coming year….

The haro and taro in the Aran Valley

In Les, the taro is erected on Saint Peter’s Day and remains there until Saint John’s Eve the following year, when it is burnt in the village square. Following the blessing, it is set on fire and a group of young people spin balls of fire (halhes) while it burns. The halhes are an important part of the celebration and are made with cherry bark bound with wire. The children whirl them around in the air over their heads, projecting sparks that brings the purifying element of fire to every corner of the village. When the halhes have burned out, the dances begin, with the local dance group dressed in colorful traditional costumes. They dance typical local dances: the Aubades, eth Tricotèr, eth Cadrilh and the Balh Plan. The night is associated with numerous symbols and beliefs and it is also a night of love, when many couples used to get engaged. The festival represents Aranese identity, and there is dancing to the music of traditional Gascon instruments that have been recovered thanks to the work of the group Es Corbiluhèrs.

In Arties, the taro is dragged through the streets and squares. To the excited cries of the public, people leap over the flames. There is also music, and festivities end in the early hours of the morning in front of the mayor’s house, where the charred taro is left. There is also a taro for children.

According to tradition, the ashes of the taro protect, purify, and fertilize, so when they are scattered throughout the village, they ward off evil spirits. The festival is accompanied by presentations of Aranese music and dances, and a community dance for the villagers.

Occitan

Occitan